DO SMALL: A Short Feature on a Parish Orientation

Do Small

A few months ago, at the Lents Commons in Southeast Portland, there was a gathering of sixty leaders from small faith-communities around the city, most of which practice some form of hyper-local, communally based church-life. It was the semi-monthly story-telling round-table for Parish Collective-Portland. The group was quite varied in its church expressions: There were “communities” of no more than four people living in neighborhood homes. There was one twenty-five year veteran of communal-living from North Portland. There were even a few pastors from more attractional-based Portland churches that came because, as one pastor stated publicly, “I am alone in my church and it is so refreshing to be with people who think like all of you do.”[1]

“Parish Collective is a growing group of churches, missional communities, and faith-based organizations which are rooted in neighborhoods and linked across cities: Edmonton, Vancouver, Seattle, Tacoma, Portland…Bellingham, Sacramento, San Francisco.”[2] The organizing principle is a geographically based ecclesiology. It is a pressing passion that the hope of the mission of Jesus Christ may very much be found in getting a “smaller” vision: a clearly defined neighborhood, a walking-world, a parish. The fact of the matter is: a mission that is too large (“we want to reach the world,” “reach a generation” or even “reach our city”) actually leads to impotence and inaction. It is little more than a virtual-mission in an increasingly rootless virtual-world. However, with a clearly defined parish, the community of faith knows what to be responsible for and where the bounds of that responsibility begin and end. As I wrote in a blog post for The Parish Collective:

For a guy like me, my soul is simply too small to wrap itself around the whole world. I am indebted to religious leaders who delegate the world out in consideration of my limited soul-space. But even a goal like, ‘Love Portland’, is more than my mind can handle. A city like Portland is a divine circus of communities, dreams, economic forces, injustices, cultures, policies, sorrows, histories and, most importantly, stories. Just thinking about it all but crashes my spiritual operating system … I want to be a part of the stories of my time, be they found on a front-porch, in a dog park, at a neighborhood association meeting, in my kid’s cafeteria, at a political rally, or simply across the table from a beautiful someone who, apart from intention, I would never otherwise know.[3]

The Parish Collective is “reaching backwards” to the parish-realities of old, when a city was divided into objective units (parishes) and each unit contained one church (parish church) and that church was responsible. That spiritual-community (clergy and lay alike) was responsible for the joys and injustices, the worshiping and caring, in fact all parts of the meaningful human life (christening, educating, marrying, burying, etc.).

Tim Soerens, one of the founders of the Parish Collective, a now three-year-old network, says:

Within the context of the neighborhood we can work out the three pillars of the compassionate and justice-practicing church. Those three pillars are ‘community’ based in a theology of the Trinity, ‘mission’ based in participation in the Misio Dei and finally, a grounded personal and communal ‘identity’ based in the Imago Christi.[4]

Once again, this network is defined more by an organizing principle then by any sort of unique theology.[5] It is the antithesis of “mega-church” or “church-growth” philosophies that reached their climax in the late twentieth century. The focus is not to grow as large as possible, nor is it to attract people from distances, which are only defined by the time consumers are willing to spend sitting in their car (as one parish leader said to me, “Everything changes when you get in your car.”[6]) The focus is to serve a very given place (clearly geographically defined) and that from that bounded space, the community of faith will experience a truly multi-dimensional and integrated wholeness, as all aspects of life are communally shared, from worship to neighborhood association meetings, from chance encounters in a local business to shared walks to and from children’s schools.

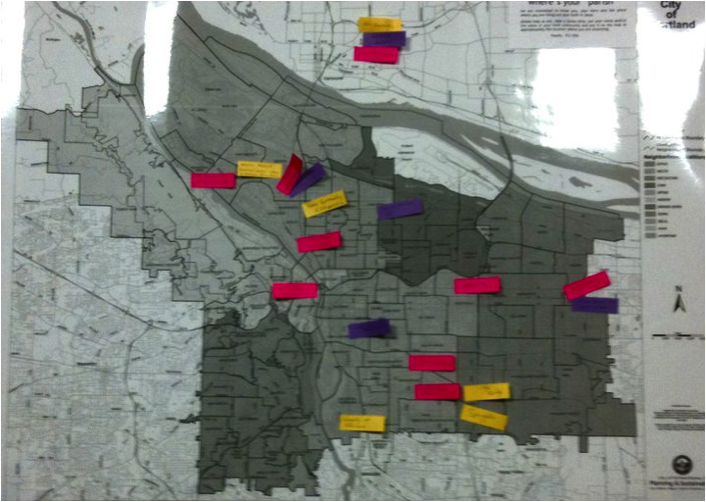

This organizational style is gaining momentum in post-Christian urban centers. At last Tuesday’s Parish Collective-Portland meeting, two dozen communities were represented and most of those had existed less than four years. Here is a map of Portland’s Eastside with some of those communities marked:

FIGURE 1. Source: Photo taken at the event.

The church is burdened today with a meaning deficit. One way of addressing this deficit is with the sort of integrated life that a parish philosophy presents (sustainable, service, shared life, simplicity), which is infusing meaning where previously many feel none existed.

This return to a parish-orientation is birthing in harmony with many trends in secular society. In the urban center of Portland, there is a growing presence of sustainability values and urban-homesteading.[7] Young families are increasingly localizing their lives. They are selling their cars, using bikes and metro services; they are buying local and patronizing neighborhood establishments (even when they cost “more”[8] than a suburban “big-box store”[9].) My neighborhood, in Portland’s urban center, has three urban-homesteading oriented stores with garden supplies, urban livestock, canning and food preservation resources, rainwater collection, and sustainable cooking services. Oxford University Press’ 2007 word of the year was “locavore.”[10] “The ‘locavore’ movement encourages consumers to buy from farmers’ markets or even to grow or pick their own food, arguing that fresh, local products are more nutritious and taste better. Locavores also shun supermarket offerings as an environmentally friendly measure, since shipping food over long distances often requires more fuel for transportation.”[11] Because of these shifting passions (and I mean “passions” as whole communities are reorienting the very way they live, spend, work, serve and schedule), one’s local coffee-shop, local pub or local shopping hub have become subjectively meaningful; which begs the assumption that soon one’s “local church” could follow in queue as a locus of subjective and integrated meaning. It is hard to explain the phenomenon of self-identification, but much of the population of post-Christian Portland identify themselves most passionately with their “village” (another term used for a walking neighborhood), as opposed to the city as a whole.

Pastor Paul Sparks of Zoe Church in Tacoma and a founder of the Parish Collective says:

the big thing I am proud of is not anything regarding numbers. Zoe members have started seven different small businesses that are their kingdom vocational callings. You can imagine the kind of social fabric that can create. It creates such amazing collaborative possibilities and irreplaceably significant to have the face of the church before the world (for bad or good): how we treat one another, social, governmental. Our best moments are beautiful moments, but our ugliness is also good for us… it is a mirror to our lives and shows the part of our lives that are untested and where our faith in Christ needs work.[12]

Tim Soerens’ Cascade Neighborhood Church, uncompromisingly rooted in Seattle’s South Lake Union, has never grown to more than twenty-five members. But of those attendees, over ninety percent are deeply involved in multiple justice and service missions in the neighborhood. Cascade Neighborhood Church has started three non-profits.[13] Many of their Sunday gatherings appear more like community-action non-profits than a church. Pastor Soerens insists that this is not a model of condescension,

Popular terms like “contextual,” “missional,” and even “incarnational” can easily be “colonial.” In my experience, there is not a lot of language about how we (the worshiping community) are going to be shaped and transformed by the world around us. In order to become truly ‘incarnational’, then you must be reshaped by your context.[14]

As you have probably already guessed, this sort of church life is in many ways the most difficult. It is very difficult to maintain and takes a tenacity of conviction and propensity for risk. Many churches begin with the rhetoric of parish, but quickly betray that vision for streamlined growth and emotionalized worship services. One local Portland church named after the specific downtown neighborhood in which they mission, seeks to reach their post-Christian “village”. It is a wonderful church with a great heart for the city. I once asked a table of the church’s leadership and committed congregants, “what percentage of your church attendants actually live your neighborhood?” The group stared at one another until one person meekly said, “Probably five percent.” He was quickly corrected by an administrative staff member who said, “The percentage actually is much smaller than that.”

Pastor Sparks’ Zoe church in downtown Tacoma was founded in 1989 and by the year 2000 had grown to over four hundred congregants. Then, in the year 2000, Pastor Sparks, out of his growing conviction for a kingdom-mission that is shaped by its context and geographically defined, began to change the vision and rhetoric of his church to embrace these parish-ways. Within two years Pastor Sparks’ church shrunk from 400 to fifteen.[15]

This is a story that I have heard time and again, as pastors commit to convictions that infiltrate their congregants’ freedom, comfort, pocket-book, and autonomy. In a world where the consumer is king and the appetites and declarations of that king are fed without temperance, the self-sacrifice and “smallness” of a parish philosophy swims against a very brisk cultural current.

A parish orientation, while ancient in its roots, couldn’t be more “new,” when one considers the ways that it strikes against many of the dominating values of our world. However, as Nietzsche famously said, “The essential thing ‘in heaven and earth’ is that there should be a long obedience in the same direction; there thereby results, and has always resulted in the long run, something which has made life worth living.”[16]

[1] Parish Collective, “Home Page,” Parish Collective, http://www.parishcollective.org/ (accessed December 5, 2010).Quote from James Worley of Powell Valley Covenant Church’s Lifechurch.tv contemporary service (located in Gresham, OR) on December 1, 2010 at the Parish Collective-Portland gathering at Lents Commons.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Tony Kriz, “A Village Conspiriacy,” Parish Collective, http://parishcollective.ning.com/profiles/blogs/tony-kriz-a-village (accessed November 23, 2010).

[4] Tim Sorens and Paul Sparks, the founders of Parish Collective, interview by author, Portland, OR, November 23, 2010.

[5] Mainline, Charismatic, Evangelical, non-Protestant and emergent communities all participate equally in the life and leadership of the Parish Collective.

[6] Quote from Eric Shreves, a leader in the “People of Praise,” a Roman Catholic founded intentional community rooted in the Kenton Neighborhood of Portland, OR.

[7] Urban Homesteading, “Urban Homestead Definition,” Urban Homesteading, http://urbanhomestead.org/urban-homestead-definition (accessed December 6, 2010).

- a suburban or city home in which residents practice self-sufficiency through home food production and storage.

- the home and garden of a person or family engaging in sustainable small-scale agriculture and related activities designed to reduce environmental impact and increase self-sufficiency.

- a name describing the home of a person or family living by principals of low-impact, sustainable self-sufficiency through activities such as gardening for food production, cottage industry, extensive recycling, and generally simple living.

[8] There are strong arguments that local shopping ultimately does not cost more since it requires less gas, wear and tear on vehicles and less time that allows for other forms of productivity. These arguments are purely economic and do not even take into account quality of life, relationally driven commerce or non-economically driven forms of life-investment (family, neighbor, volunteerism, church, etc.).

[9] “Big Box Store” is a euphemism for high-volume mega stores. The name is derived from the fact that most of these stores are found on huge lots and the store itself looks like a “big box.” Many stores meet the criteria of “big box” from Ikea to Home Depot. Walmart is the most notorious. This conglomerate system of product distribution is critiqued for at least three reasons: destruction of local economies, unjust product acquisition (including slavery and ecological destruction) and poor employee care.

[10] Oxford University Press Blog, “Oxford Word Of The Year: Locavore,” Oxford University Press Blog, http://blog.oup.com/2007/11/locavore/ (accessed December 6, 2010).

[11] Ibid.

[12] Paul Sparks, interview by author, Portland, OR, November 23, 2010.

[13] Cascade Neighborhood Church has also planted two other neighborhood based churches in their three and a half years of existence.

[14] Tim Soerens, interview by author, Portland, OR, November 23, 2010.

[15] Paul Sparks, interview by author, Portland, OR, November 23, 2010. These statistics were received directly from Pastor Sparks.

[16] Friedrich Nietzche, Beyond Good and Evil

It’s really a nice and helpful piece of information. I’m glad that you shared this helpful info with us. Please keep us informed like this. Thanks for sharing.